This article is the second in a series of investigations examining the narrative surrounding the ‘Cartel de los Soles.’

Guacamaya, September 8, 2025. Just last week, the U.S. military attacked an alleged drug trafficking boat in international waters, coinciding with a Navy deployment in the Caribbean near Venezuela’s shores. Officially, this operation aims to combat drug trafficking attributed to the Cartel de los Soles and the Tren de Aragua, supposedly led by Nicolás Maduro.

In our recent investigation, we discussed how claims against the Cartel de los Soles lack substantial evidence and serve political objectives instead. But why are these allegations gaining traction? Who benefits from their promotion? And why is this happening now?

Initially, promoting the Cartel de los Soles narrative was an easy task for some cynical opposition figures in Venezuela. They believed anything was justifiable if it could help topple Hugo Chávez first and then Nicolás Maduro. If claiming Venezuela was a ‘narco-state’ could lead to U.S. military intervention, they would go for it.

In the U.S. and other countries across the Americas, however, this narrative has been manipulated for economic and domestic political gains, often unrelated to the liberation of Venezuelans from tyranny. For many years, it has supported electoral campaigns in South Florida and aligned with the interests of big oil. More recently, it has entwined itself with Donald Trump’s agendas of mass deportations and military efforts against drug trafficking.

Navy Deployment: A Strategy for Regime Change

Currently, there are no shocking drug-related scandals involving Venezuela. The fentanyl crisis is the most pressing issue in the U.S., accounting for 70% of overdose-related deaths in 2023. Issues like the opioid epidemic and escalating cartel violence in Mexico should take priority, yet Venezuela seems unrelated, right?

Cocaine seizures reported by the DEA have increased steadily at the southeastern border—about 37.6% from 2022-2025. Meanwhile, in the ‘Coastal/Interior’ region, including urban centers like Chicago, seizures dropped by 54.2%. It seems peculiar that Washington, DC, would focus on a Caribbean operation instead of prioritizing the Mexico land border, where the bulk of cocaine smuggling and routes for fentanyl and other narcotics exist.

The Navy is deploying at least 8 warships, a nuclear-powered submarine, and a Marine Expeditionary Unit in the Caribbean, surrounding Venezuela’s territorial waters. The USS Iwo Jima, part of an Amphibious Ready Group, is included in this deployment. Photo: Michael N. Minkler / U.S. Navy.

The Navy is deploying at least 8 warships, a nuclear-powered submarine, and a Marine Expeditionary Unit in the Caribbean, surrounding Venezuela’s territorial waters. The USS Iwo Jima, part of an Amphibious Ready Group, is included in this deployment. Photo: Michael N. Minkler / U.S. Navy.

Furthermore, the recent U.S. Navy deployment in the Caribbean lacks effective capabilities for combating drug trafficking. Mark Cancian, a senior advisor on defense and security at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and retired U.S. Marine Corps colonel, states it’s merely ‘political signaling.’

‘The ships lack law enforcement authority, unlike the Coast Guard, which typically conducts counter-drug operations,’ Cancian elaborates. ‘They are powerless ashore without host country consent. The attention garnered by this exercise was intended.’

A former senior Pentagon official revealed to Guacamaya that the Navy’s deployment isn’t a robust counter-narcotics effort; rather, it may be a show of force to gauge whether any Venezuelan military personnel would reach out to the U.S. for a potential coup against Maduro. ‘Currently, no external parties have strong ties with Venezuelan generals, not even Brazil or Colombia, so building connections is essential.’

The Navy deployment is not aimed at combating drug cartels; it’s a purely political move manipulated by interest groups seeking to use the U.S. military for regime change in Venezuela. To clarify this, we must explore the origins of the Cartel de los Soles narrative and its resurgence in the U.S. in both 2020 and now in 2025.

The Origins: Displaced Elites Push for U.S. Intervention

Firstly, we need to recognize that as soon as Chávez assumed power, Venezuela entered a phase of extreme political polarization. While Chávez pursued radical reforms, many elites and middle-class citizens concluded he had to be ousted at all costs.

Chávez took office in January 1999. By 2002, he faced a military coup, and in 2004, a significant strike by executives in the oil sector ensued. In that same year, María Corina Machado, currently a significant opposition figure, accused Chávez of manipulating the votes in a referendum, despite the Organization of American States and the Carter Center verifying the absence of evidence to support this claim.

In 2005, María Corina Machado, then director of the civil society group Súmate, met President George W. Bush in the Oval Office. She gained prominence in 2004 for alleging electoral fraud, contradicting facts presented by the Carter Center and the Organization of American States. Photo: Eric Draper / White House.

In 2005, María Corina Machado, then director of the civil society group Súmate, met President George W. Bush in the Oval Office. She gained prominence in 2004 for alleging electoral fraud, contradicting facts presented by the Carter Center and the Organization of American States. Photo: Eric Draper / White House.

Herein lies a major issue. Reasonable individuals should have refuted these absurd theories; however, if the priority was to end Chavismo, many thought it best to allow those lies to proliferate.

Thus, opposition activists leveraged authentic cases of high-ranking officials complicit in drug trafficking—a regional issue, as we explored in the previous piece—to fabricate a political narrative around a ‘narco-state.’ Nevertheless, thus far, they have failed to provide evidence of a cohesive, hierarchical cartel they assert exists. Interestingly, none of the DEA National Threat Drug Assessments have ever mentioned the so-called Cartel de los Soles. Amidst this backdrop, it became acceptable to make virtually any claim, regardless of absurdity, as long as it targeted the government.

In *Boomerang Chavez* (2015), Emili J. Blasco claimed that the Venezuelan state under Chávez allegedly directed ‘up to 90% of Colombia’s cocaine production towards the United States and Europe.’ However, the author failed to provide any supportive evidence, not even an anonymous sourcing. Despite this, the claim was regurgitated by Chávez and Maduro’s opponents, as it aligned with their political motives. This assertion is cited in the Wikipedia page about the Cartel de los Soles. Yet, we can refute this claim. The Consolidated Counterdrug Database estimates that between 2012-2019, only 1,376 tons (10%) flowed out of Venezuela compared to 13,703 tons from Colombia.

Often, people and organizations spread misinformation accidentally, failing to verify facts before dissemination. Transparencia Venezuela, an anti-corruption watchdog, claimed in a 2024 report that, ‘according to a DEA report, almost 24% of global cocaine production transits through Venezuela.’ Should Colombia have produced at least 2.644 tons of cocaine, that would imply 639 tons originating from Venezuela. The organization went on to estimate the scale of Venezuela’s drug trade based on this inaccurately interpreted assertion.

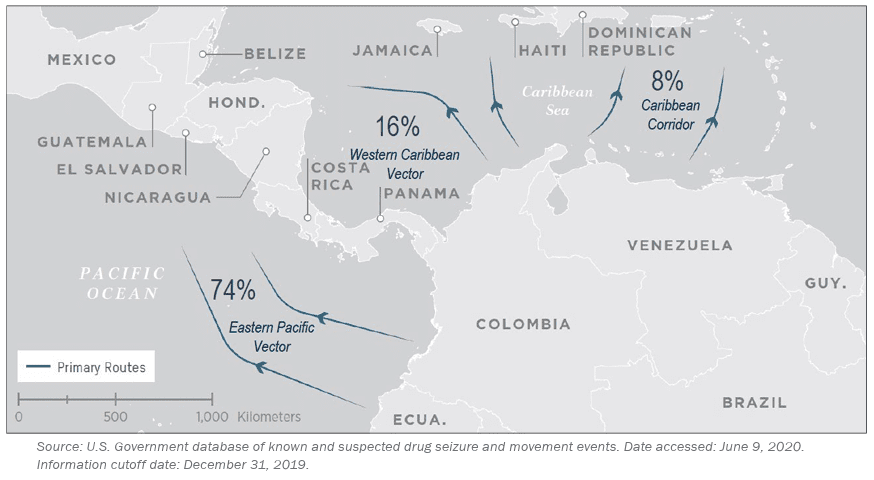

However, the DEA never made such a statement. Instead, the NGO cited an article that misconstrued the DEA 2020 National Drug Threat Assessment, which indicated that 16% traversed the ‘Western Caribbean vector’ and another 8% through a different ‘Caribbean corridor.’ The illustrative map below suggests only one corridor closely aligns with Venezuela’s geographic location, yet the report does not denote that any of these vectors is specific to the country.

A DEA map highlighting primary cocaine trafficking routes from South America to North America. Image: Drug Enforcement Administration.

A DEA map highlighting primary cocaine trafficking routes from South America to North America. Image: Drug Enforcement Administration.

The report from Transparencia Venezuela arrived at the conclusion that ‘it may be assumed there was a gross income of USD 8.236 billion in 2024’ for the country. Yet, this estimate is solely based on erroneous premises. This figure has since been utilized by Maduro’s adversaries to assert that narcotics trafficking is more lucrative than oil, which dominates the economy. Hence, they argue Venezuela must be a narco-state in desperate need of international intervention, specifically from the U.S.

Branding Venezuela as a narco-state carries severe implications. It has been employed to invoke the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance (known by its Spanish acronym, TIAR). The premise is that, given Venezuela is a failed state overtaken by criminal organizations, intervention by governments across the Americas, led by the U.S., is both legally and morally justified. For some in Venezuela’s opposition, like Machado and Iván Simonovis, this has seemed like the best course of action—getting Uncle Sam to remove Maduro.

David Smilde, a sociology professor at Tulane University in New Orleans, has studied Venezuela for over 30 years and authored five books on the topic. ‘This phenomenon represents a classic method by marginalized elites to regain power in authoritarian settings, particularly when they cannot do so through elections or protests,’ he explained. ‘They’ve attempted this for years, claiming Venezuela hosts terrorist camps or Iranian missiles, poses a threat to regional stability, or is a national security risk to the U.S. They leverage their access to international media and sympathetic think tanks to propagate these narratives.’

In the July 2024 presidential election, the opposition claimed a 37-point victory margin, backing it up with voting machine receipts. Yet, Maduro continued to declare victory and maintain his power. Following this, Machado, alongside her allies, embarked on a media and lobbying campaign to summon international pressure to oust him, branding him as the leader of the Cartel de los Soles.

However, merely pushing a narrative by some Venezuelan politicians isn’t enough. Economic and political factions within the U.S. have adopted this storyline to further their own interests at specific moments.

‘Officials in the State Department and staffers on Capitol Hill are frequently approached by individuals with outlandish ideas advocating U.S. intervention in their home countries,’ Smilde observed. ‘They usually dismiss these suggestions, but occasionally they align with their agendas. Some of Venezuela’s opposition figures remind me of Ahmed Chalabi, the Iraqi politician who lobbied for the notion that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction, necessitating military action. We later revealed that much of the information he provided was false.’ Chalabi went on to guide the political transition post-2003 invasion and was subsequently appointed Minister of Oil and Deputy Prime Minister. However, he was not operating in isolation; his claims dovetailed with the designs of the George W. Bush administration.

Failed Regime Change Plans in 2020

When did the Cartel de los Soles concept truly take root in the U.S.? We can trace it back to March 2020 when the Justice Department first indicted Maduro and other senior officials. This coincided with the Trump administration’s ‘maximum pressure’ strategy aimed at effecting regime change in Venezuela.

In fact, this was at a time when the campaign was beginning to lose steam. Between 2017 and 2020, the U.S. Treasury imposed and tightened sanctions on Venezuela’s financial and oil sectors, severely harming its economy. In January 2019, Washington, DC, recognized Juan Guaidó, speaker of the National Assembly, as the legitimate president, supporting the formation of a parallel ‘Interim Government.’ As President Trump stated at the time, ‘all options are on the table,’ alluding to potential military action.

In January 2019, then National Security Advisor John Bolton was featured on TV, holding a notepad with ‘5,000 troops to Colombia’ amid rising tensions with Venezuela, as the U.S. sought to execute regime change alongside the figure of an ‘Interim Government.’ Photo: CNN.

In January 2019, then National Security Advisor John Bolton was featured on TV, holding a notepad with ‘5,000 troops to Colombia’ amid rising tensions with Venezuela, as the U.S. sought to execute regime change alongside the figure of an ‘Interim Government.’ Photo: CNN.

However, a shift occurred by the end of that year. With regime change unachieved, Guaidó’s popularity began to wane. While many Venezuelans remained opposed to Maduro, they were no longer willing to support the self-proclaimed ‘interim president.’

In early 2020, the Trump administration deliberated on the possibility of military intervention in Venezuela, as former Defense Secretary Mark Esper recounts in his book, *A Sacred Oath: Memoirs of a Secretary of Defense During Extraordinary Times* (2022). This strategy was proposed by National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien and Mauricio Claver-Carone, Senior Director for Western Hemisphere Affairs. Nevertheless, Esper and other cabinet members were disinclined to risk American lives and resources for this cause, particularly given that they believed many vital contingencies were overlooked.

Ultimately, Attorney General William Barr successfully redirected President Trump’s focus, asserting it would be better to ‘stop the flow of drugs to the United States, especially from Venezuela.’ The president opted for this less costly approach. O’Brien and Claver-Carone eventually acquiesced, ‘they desired more but were content that we shared a desire to pursue more significant actions after years of inaction,’ Esper writes.

In practical terms, the outcome was that the Justice Department indicted Maduro, Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino, and prominent regime figures like Diosdado Cabello, offering rewards of up to $10 million for information leading to their capture. The U.S. deployed Navy and Air Force units to the Caribbean under the pretense of a counter-narcotics operation. Although it failed to significantly combat drug trafficking, it attracted media attention. This outcome aligns with what President Trump consistently favored during both presidential terms, as noted by Esper in his book.

However, the U.S. military took no action within Venezuela itself. Naturally, not everyone was pleased. Exiled opposition members attempted to instigate an armed intervention by sending mercenaries and army defectors into the country, led by former Green Beret Jordan Goudreau, which became known as Operation Gideon. The operation collapsed upon landing, resulting in six deaths and 91 captures. Esper suggests in his account that Claver-Carone and O’Brien were aware of the plans, while there are unconfirmed reports that some U.S. agencies may have known about or been involved in the preparations, although not at the direction of President Trump.

Summing it all up, the objective behind promoting the Cartel de los Soles narrative then was about orchestrating a strategic retreat. The idea was to showcase the Trump administration’s tough stance against Maduro, using U.S. military might to intimidate him without actually causing harm.

Geoff Ramsey, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, pointed out that while the year 2020 began with Maduro’s indictment, ‘by year-end, Trump expressed regret over supporting the Interim Government and indicated openness to meeting Maduro,’ as reported in this Axios interview.

Reviving Regime Change Plans in 2025

Much has shifted since 2020. However, the resurgence of the Cartel de los Soles narrative in 2025 can be largely tied to similar motivations. Even while President Trump expresses skepticism toward the idea and seeks distance from Venezuela’s opposition, other influential voices in Washington remain supportive.

Secretary of State and National Security Advisor Marco Rubio has long championed regime change in Venezuela. His political career has been bolstered by the Cuban-American exiled community, which has recently welcomed Venezuelan elites from South Florida. The same applies to his congressional allies like Carlos Giménez, Maria Elvira Salazar, and Mario Díaz-Balart, along with lobbyists-turned-politicians like Mauricio Claver-Carone, remember him?

La noche no será eterna.

Libertad para Cuba

Libertad para Venezuela

Libertad para Nicaragua

Libertad para Nuestra América

God bless the USA! 🙏🏻🇺🇸

— Rep. Carlos A. Gimenez (@RepCarlos) September 2, 2025

Not all are Republicans; longtime Democratic Senator Robert Menéndez, though he has recently fallen from favor after being indicted and subsequently convicted of receiving bribes from a foreign government. Frequent allies have found common ground with ‘hawks‘ or ‘neoconservatives’ who, contrasting with President Trump, are eager to meddle in other countries’ internal matters, such as John Bolton and Elliot Abrams, key advocates of regime change in Venezuela back in 2019.

Within the closely-knit Cuban-American political community, the goal is to liberate the homeland from communist rule while other domestic issues are secondary. This community can be viewed as having one of the least effective lobbies in history; they can impose strict sanctions on Cuba, yet have not sparked political change in over six decades.

Venezuela’s role is significant for them. They believe both regimes rely on each other for survival; Havana requires Venezuelan oil while Caracas depends on Cuban intelligence. With their repeated failures to dethrone the Castros, the South Florida clique has increasingly focused on Venezuela, where they perceive potential success as more attainable.

Now, a crucial aspect is that Rubio has adapted his rhetoric to align with President Trump’s language, positioning intervention in Venezuela within the America First framework. How? By arguing that the nation is governed by a narco-terrorist organization posing a threat to U.S. national security. Therefore, instead of moving against a foreign government, it becomes about targeting the Cartel de los Soles.

This strategy has led to contradictory outcomes. Rubio, along with his Cuban-American and Venezuelan allies, advocating for intervention would find themselves entangled amid these contradictions. The Trump administration has, as a consequence, adopted the Cartel de los Soles and the Tren de Aragua narrative as operational mechanisms, not to induce regime change, but to enforce a robust immigration agenda. The narrative here contends that former President Joe Biden’s policy permitted terrorist gangs to infiltrate the U.S., necessitating their return home.

Shortly into his third month in office, President Trump invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to accelerate the deportation of Venezuelan migrants, suspending their due process rights, and transported 250 of them to El Salvador. ‘The Cartel de los Soles narrative has been advanced by certain Venezuelan opposition figures to advocate for intervention, but Trump has repurposed it to demonize Venezuelan immigrants,’ Smilde explained.

For the Cuban-American political sphere, this represents a challenging pitch. The same administration seeking to end special immigration protections for Venezuelans and Cubans, including Temporary Protected Status and Humanitarian Parole. Voters will reflect U.S. citizens, as will the majority of contributors. Nonetheless, many in this community have friends and relatives impacted by the sudden immigration policy shifts, putting their supposedly safe House seats at risk.

Un mensaje de esperanza para los venezolanos:

Acabo de presentar la propuesta bipartidista – Ley de TPS para Venezuela 2025.

¡Protección, dignidad y estatus legal hasta que Venezuela sea libre! pic.twitter.com/YscRCTVIiN

— María Elvira Salazar 🇺🇸 (@MaElviraSalazar) May 10, 2025

Geoff Ramsey noted that the Trump administration is addressing Venezuela through two fronts. Initially, there’s an approach tailored ‘for the cameras.’ Deploy the military and carry out strikes against drug trafficking vessels. The second angle aims at ‘advancing U.S. interests regarding immigration, energy, and other strategic issues.’

After the Treasury revoked licenses for oil firms to operate in Venezuela, it granted a new one on July 24, permitting Chevron to resume local operations. Deportation flights to the South American nation from the U.S. continue to operate with a twice-weekly frequency.

President Trump is also utilizing the military to address domestic political and law enforcement matters, affording him greater executive maneuverability and significant media attention. This includes not only the Navy’s Caribbean deployment, but proposals to attack cartels within Mexico, and employing the National Guard to combat crime in Washington, DC, and crack down on protests in Los Angeles. ‘Maduro has similarly employed force, as seen in his offensive against crime dubbed Operación Liberación del Pueblo,’ Smilde remarked.

Interestingly, right after the issuance of the new Chevron license, on July 25, the U.S. Treasury designated the Cartel de los Soles as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist, although it did not name specific individuals or entities. This move was followed by an increase in the bounty on Maduro, rising to $50 million.

‘There’s a reason why Trump focused on the Tren de Aragua (TdA), not the Cartel de los Soles,’ Ramsey pointed out, referring to the recent airstrike targeting a boat believed to be carrying drugs from Venezuela. ‘Trump aims to deport hundreds of thousands of Venezuelan migrants, justifying this by invoking the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, asserting that the TdA is invading the country.’ The subsequent necessity is linking the gang’s operations to Maduro, thus equating it to an invasion by a foreign nation.

‘TdA is designated as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO), meaning anyone accused of materially supporting them can face prosecution under U.S. laws,’ Ramsey explained. ‘Conversely, the Cartel de los Soles received a milder Treasury Department designation. This likely reflects the U.S. ambition to create space for Chevron and other companies to operate in Venezuela without being perceived as materially supporting a terrorist faction.’

When questioned about the rationale for the Trump administration’s dual-pronged approach, Ramsey conveyed that ‘a significant number of individuals are exasperated by the prospect of loosening sanctions and the cessation of Temporary Protected Status for Venezuelan migrants, as the priority shifts to pushing an immigration agenda.’ Hence, these visible efforts would portray concern without jeopardizing the core objectives.

Meanwhile, the military deployment may represent one facet on which the entire administration can reach an agreement,’ stated the former Pentagon official. While Rubio may try to exploit it for regime change, America First advocates believe the U.S. government is taking a firm stance on crime.

The Economic Drivers Behind The Narrative

Economic interests also play a significant role. Venezuela is known for housing the world’s largest oil reserves, with 303 billion recoverable barrels of crude—representing 17.5% of the world total. Additionally, it possesses the seventh-largest natural gas reserves and considerable deposits of gold, iron, coltan, tin, bauxite, tantalum, and platinum.

In the past year, María Corina Machado has marketed Venezuela as a ‘1.7 trillion dollar opportunity’ awaiting Maduro’s ousting for realization. She has virtually attended various significant international business gatherings to promote this narrative, including CERA Week 2025, an energy conference in Houston. Therefore, it’s not surprising that economic interests would support the regime change proposition.

Now we already know some usual players. Notably, Chevron lobbies for a permit to operate in Venezuela, intending to recover its investments and debts. Yet, ExxonMobil has been actively involved, lobbying and funding think tanks on Venezuela-related issues.

The largest U.S. oil firm and the Chavistas have a long-standing antagonism. ExxonMobil exited Venezuela following Chávez’s enforced reforms, mandating private oil companies accept a majority stake held by state-owned PDVSA. Initially, the corporation argued that this nationalization was unlawful; however, an arbitration tribunal concluded it was legal, despite ExxonMobil receiving close to $1.6 billion in compensation. It wouldn’t be surprising if ExxonMobil aimed for a return. Furthermore, it has expanded its operations in nearby Guyana, providing multiple billion incentives for nurturing a weakened and isolated Venezuela.

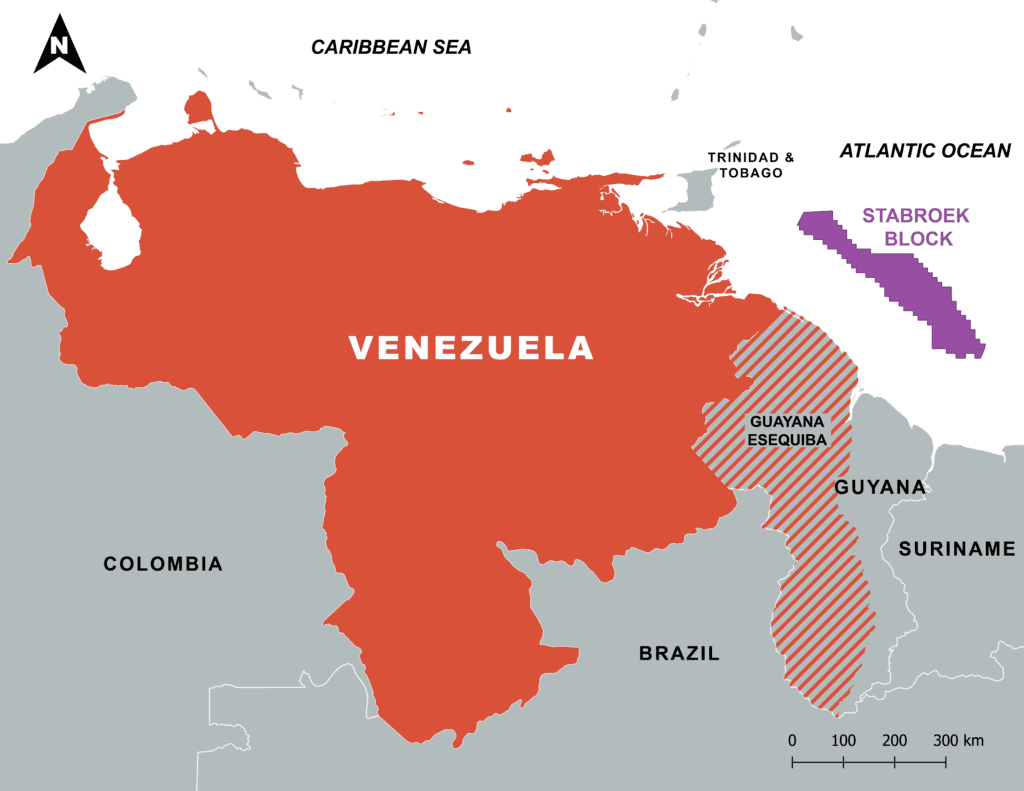

Guyana is embroiled in a territorial dispute with Venezuela, which gains relevance for one significant reason. The waters adjoining the contested Essequibo region are estimated to hold 11 billion barrels of light oil within the Stabroek offshore block. The exploitation of these resources has rapidly transformed Guyana from one of South America’s poorest nations to the wealthiest based on GDP per capita over just five years.

This is a detailed map illustrating the boundaries of the Guayana Esequiba region, with the geographical location of the Stabroek oil block distinctly marked. The map also reflects Suriname’s claim over the Tigri territory, which is controlled de facto by Guyana.

This is a detailed map illustrating the boundaries of the Guayana Esequiba region, with the geographical location of the Stabroek oil block distinctly marked. The map also reflects Suriname’s claim over the Tigri territory, which is controlled de facto by Guyana.

ExxonMobil leads a consortium within Stabroek alongside Hess (recently acquired by Chevron) and CNOOC. The success of the oil block, and consequently Guyana, relies on maintaining the territorial dispute. Military conflict appears improbable; however, what if there were an initiative aimed at negotiating a peaceful conclusion? This could lead to a division of royalties or managed in an escrow account. Alternatively, should Caracas impose regulations, the consortium may lose its favorable government terms. These scenarios could materialize if, God forbid, Venezuela’s relations normalize.

In 2017, during the initial imposition of sectoral sanctions by the first Trump administration, Rex Tillerson, a former ExxonMobil CEO, served as Secretary of State. Remarkably, the U.S. corporation was then executing the first phases of the Stabroek project, setting the stage for a significant economic boom in Guyana starting in 2020.

Guyana is also where we find Mauricio Claver-Carone, the very individual who was advocating for military action against Venezuela. Hailing from the Cuban-American political milieu, he also manages the LARA Fund, with investments in Guyana, betting on the nation’s rapid economic success.

Spreading the Cartel de los Soles narrative aids the Cuban-American faction in South Florida in redirecting attention from their failures. Furthermore, it assists economic entities in preventing normalization with Caracas, which could jeopardize profits linked to the Stabroek offshore oil project.

Venezuela as a Scapegoat

As we’ve observed, for certain interest groups, the narrative is not so much about regime change, but rather a scapegoat and virtue signaling. We’ve elaborated on how the South Florida cabal has flourished through vilifying regime in Cuba and Venezuela. Other political and economic interests have also latched onto the Cartel de los Soles narrative as a means of gaining favorable public sentiment. ‘Nicolás Maduro is arguably the most stigmatized and discredited figure. Nobody will argue he’s a “good guy.” Therefore, one can make virtually any assertion regarding him without repercussions,’ Smilde remarked.

In several Latin American nations, the Cartel de los Soles and Tren de Aragua narratives have proven useful for some politicians. As a result, governments in Paraguay, Ecuador, Argentina, and Peru have recently dubbed the alleged group a ‘narco-terrorist organization.’ If Maduro’s criminal enterprise has been endangering regional peace for more than a decade, why the sudden urgency?

The timing here is significant: the State Department is rallying support for regional capitals to adopt this declaration. So far, presidents closely aligning with Marco Rubio have been quick to comply, whereas others like Colombia’s Gustavo Petro and Mexico’s Claudia Sheinbaum have dismissed the Cartel de los Soles narrative as unfounded.

Notably, Colombia promoted this narrative from 2019 to 2022, during Iván Duque’s presidency, while leading a Washington-backed attempt to isolate Maduro. He made the damaging decision to sever all ties with Venezuela, halting border activities. Upon Petro’s election, he shifted toward a more realistic stance, reopening diplomatic and trade relations, while refraining from unfounded assertions regarding the Cartel de los Soles. Thus, it appears curious that Colombia’s government only recognized such a notorious group as a threat after three years of silence.

Moreover, these narcoterrorism designations serve political purposes within the respective countries. In Ecuador, the ruling party exploited this issue to imply that the opposition is allied with Maduro’s alleged criminal factions, namely the Cartel de los Soles and Tren de Aragua. This same tactic aims to cast Venezuelan migrants as scapegoats for the rising crime rates, primarily associated with the reallocation of global cocaine trafficking routes towards Ecuador. Coinciding with the designation, Ecuador’s National Assembly voted to terminate a migration agreement with Venezuela.

This poses yet another challenge for Latin America: scapegoating Venezuelan migrants and condemning Maduro represent low-cost methods to increase polling figures in the region. This, of course, aligns with the U.S. State Department’s pressures to isolate Venezuela once more. Wouldn’t it be more prudent for political leaders to tackle inequality or cooperate on security matters, with genuine backing from Washington, DC?

Time to Reconsider Our Approach

‘Marco’s War’ is how various commentators describe the U.S.’s escalating confrontational stance towards Venezuela. Secretary of State Rubio has indeed embraced the misleading ‘Cartel de los Soles’ narrative as a ruse to garner backing for discredited and harmful neoconservative policies. This investigation, our second on the subject, elucidates the genuine forces shaping U.S. policy toward Venezuela—and no, it isn’t about enhancing American national security; constructive engagement, not extrajudicial killings and reckless rhetoric aimed at regime change, serves U.S. interests far better.

Our third investigative report will soon delve into the repercussions of the sharp neoconservative shift in U.S. Venezuela policy, including the empowerment of foreign adversaries, harm to the U.S. energy sector, and significant erosion of American diplomatic standing in Latin America.