Guacamaya, September 4, 2025. On July 25, 2025, the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) labeled the so-called “Cartel de los Soles (Cartel of the Suns)” as a “Specially Designated Global Terrorist Organization.” By August 7, the State and Justice Departments raised the bounty on its purported leader, Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro, from $25 million to $50 million.

On September 2, the U.S. military destroyed a speedboat in a precise strike in international waters, claiming it was transporting drugs from Venezuela along with 11 members of the Tren de Aragua gang. Despite concerns over legality and effectiveness, the administration stood firm that this was a move against a “narco-terrorist” group.

A $10 million reward was initially announced in 2020, coupled with serious allegations against the supposed Cartel de los Soles. The ongoing assertion is that Maduro isn’t acting as a head of state but as the leader of a criminal network, identified as a “narco-terrorist” for allegedly attempting to “flood the United States with cocaine.” To achieve this, it’s claimed that Maduro had previously collaborated with Colombian guerrillas, which were later substituted by the Tren de Aragua during the Trump administration.

This investigative work reveals that the accusations made by State and Justice in both 2020 and 2025 are unsubstantiated. While some cocaine smuggling routes do pass through Venezuela—with the aid of corrupt officials and military members—there’s no solid evidence proving that Maduro leads a drug trafficking operation or deliberately sends cocaine to the U.S.

In reality, Venezuela shows a regional phenomenon of lucrative illegal economies that exploit poverty and weak institutions—both of which are markedly prevalent in this South American nation. Currently, Venezuela is still a minor player in the cocaine trafficking landscape compared to other routes, such as those through the Eastern Pacific, Mexico’s land border, and the Brazilian Amazon.

A “Cartel of the Sun”

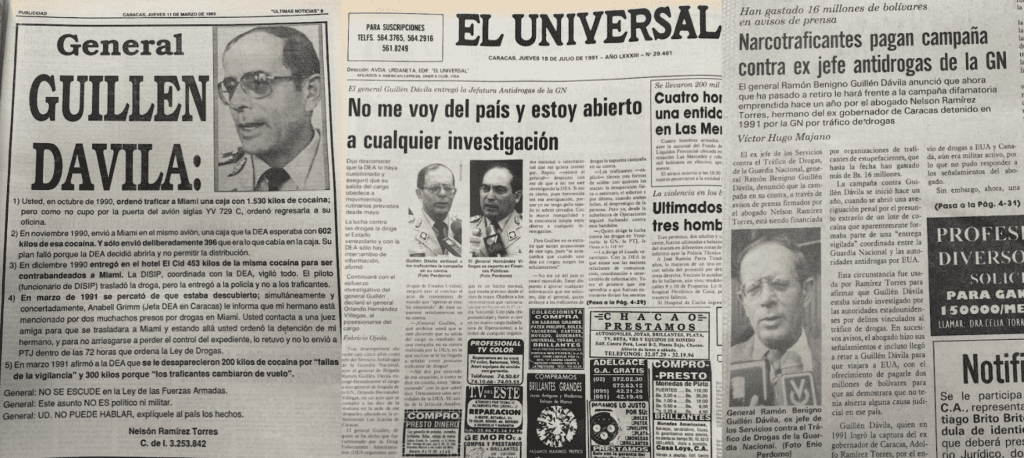

The term Cartel de los Soles emerged in Venezuela back in 1993—well before Chávez took office—due to investigations and arrests involving two National Guard generals accused of trafficking cocaine into the U.S. The individuals in question were Ramón Guillén Dávila, who led the anti-drug office, and his successor, Orlando Hernández Villegas.

The label “Cartel del Sol” came from the insignias of brigadier generals; both Guillén Dávila and Hernández Villegas wore a sun-shaped badge representing their rank. Instead of denoting a unified organization like the Medellin or Sinaloa cartels, it evolved into a journalistic term describing corruption within the military, where officers were bribed by criminal entities to facilitate the smuggling of narcotics and other illegal goods, including gold.

Reports from the Venezuelan newspaper El Universal in the early 1990s discuss the cases against Ramón Guillén Dávila and Orlando Villegas Hernández. Image: Guacamaya.

Reports from the Venezuelan newspaper El Universal in the early 1990s discuss the cases against Ramón Guillén Dávila and Orlando Villegas Hernández. Image: Guacamaya.

This initial case gained notoriety beyond Venezuela. The then-DEA Administrator, Robert C. Bronner, made allegations that the CIA collaborated with Guillén Dávila to smuggle at least a ton of cocaine into the United States. Though controlled smuggling operations for intelligence purposes aren’t rare, Bronner asserted that he was not informed about this operation.

In November 1993, 60 Minutes aired a segment titled “The CIA’s Cocaine,” featuring interviews with Bronner and Guillén Dávila. The discussions suggested that no actionable intelligence resulted from this operation, while the ton of cocaine nevertheless flooded American streets.

This case turned into a major scandal, with media coverage highlighting a “worst breakdown” in communications between the agencies, ultimately benefitting Pablo Escobar’s Medellín Cartel, as reported by Los Angeles Times, Tampa Bay Times, CBS, and Bogotá’s El Tiempo.

Investigations into Guillén Dávila and Hernández Villegas were eventually dropped during Carlos Andrés Pérez’s presidency. No charges were filed in the U.S., despite two CIA officers resigning under pressure.

Later, under Hugo Chávez (1999-2013) and his successor Nicolás Maduro (2013-present), the concept of the Cartel de los Soles began to signify something entirely different. In the time of extreme polarization since their ascendancy to power, accusations emerged against both leaders, claiming they not only enabled but led drug trafficking organizations. Although lacking conclusive evidence, these assertions gained popularity among their opponents.

But how much truth is there to this? To what extent is Venezuela pivotal in the cocaine supply chain? Is there a substantial link between this country and the U.S.? How are civilian and military officials implicated? How much of this reflects a regional pattern, compared to being unique to Venezuela?

The Cocaine Map

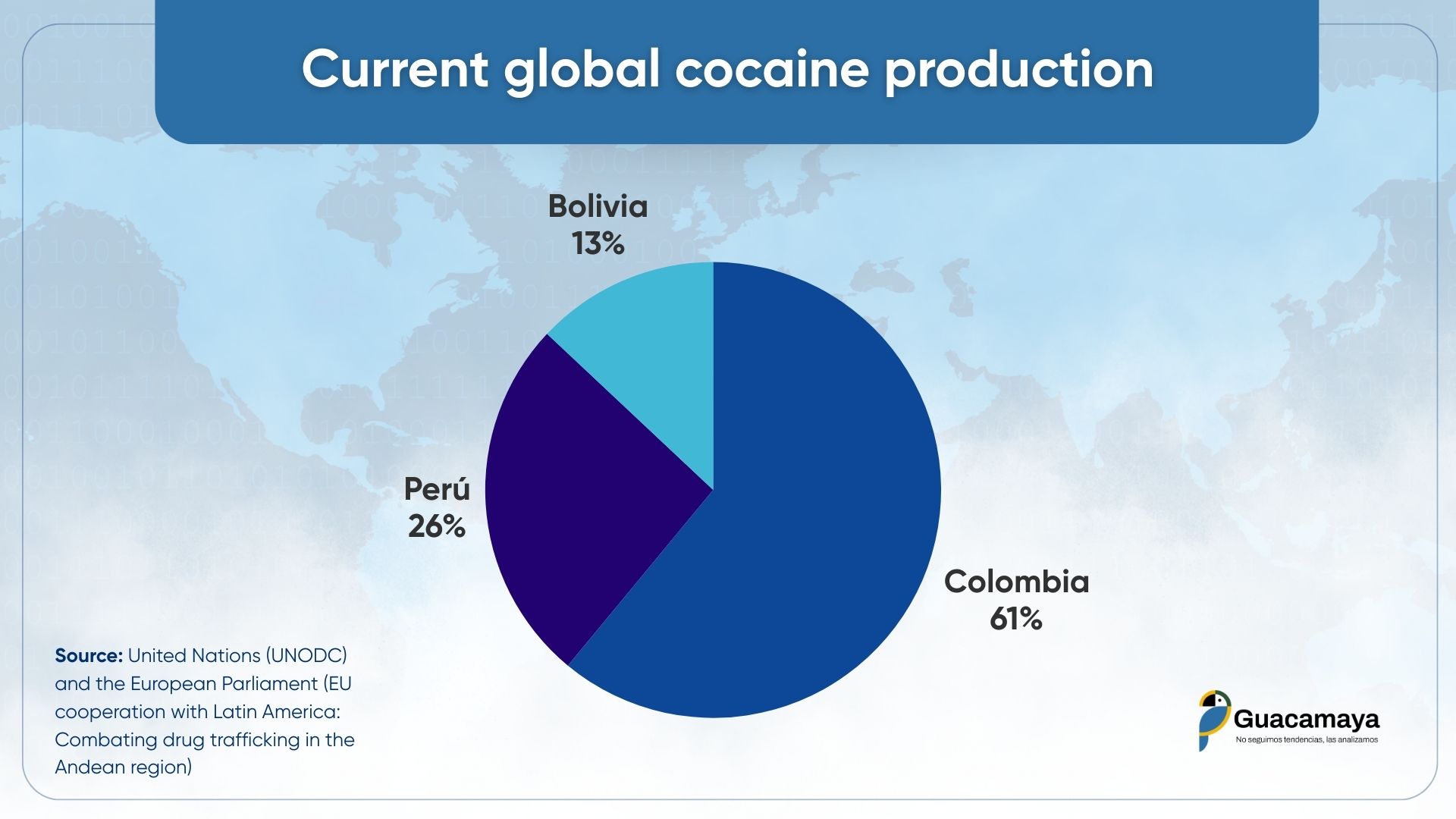

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime shows that nearly all cocaine produced globally comes from Colombia (61%), Peru (26%), and Bolivia (13%). These three Andean countries benefit from an optimal humid, tropical climate at specific altitudes ideal for cultivating coca plants.

Some production has been reported in neighboring countries like Chile, Ecuador, and Venezuela, but these figures are insignificant on a global scale. In Venezuela, armed forces have occasionally uncovered and dismantled labs in the Zulia state, particularly in the remote Catatumbo region, which spans the Colombian border, the leading producer worldwide.

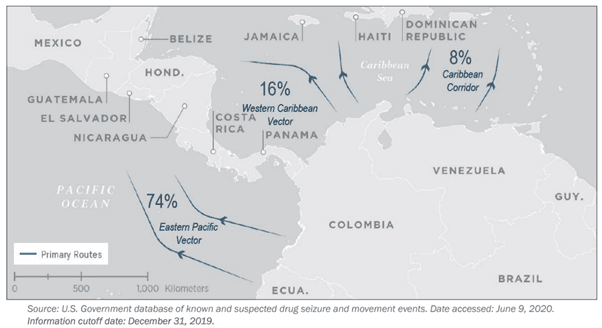

Key export routes link the three Andean nations to their main markets: North America and Western Europe. In the initial cocaine boom of the 1970s and 80s, the Caribbean served as the most direct route from Colombian producers to Miami. However, with escalating surveillance, traffickers have shifted their routes over the years.

Europe has emerged as the largest consumer, escalating by a staggering 416% over the past decade, transforming ports in Ecuador and Brazil, such as Guayaquil, Manaus, and Belém, into centralized hubs. Simultaneously, routes heading towards the U.S. have pivoted towards the Pacific Ocean and the Mexican land border—especially benefitting from trade agreements established in 1992.

Within this framework, Venezuela doesn’t stand out as a top producer or exporter. It provides a minor corridor due to its geographic positioning nestled between the leading producer and the extensive Caribbean coastline. Its porous and isolated borders with Colombia and Brazil allow irregular groups to traverse freely, taking advantage of frail institutions to corrupt local authorities.

The DEA’s 2019 report noted that 90% of cocaine bound for the U.S. traversed through Eastern Pacific (74%) and Western Caribbean (16%) routes, navigating through Central America and Mexico. The Eastern Caribbean, where Venezuela’s coastline falls, accounted for merely 8%. Earlier statistics from 2015 to 2017 show similar distributions.

A DEA map illustrates the primary vectors for cocaine transportation from South America to North America. Image: Drug Enforcement Administration.

A DEA map illustrates the primary vectors for cocaine transportation from South America to North America. Image: Drug Enforcement Administration.

It’s important to note that National Drug Threat Assessments don’t provide a precise estimate of the share of the narcotics trade flowing through Venezuela—contrary to a baseless assertion that “almost 24% of the world’s cocaine production transits through” this country.

A study from the Washington Office for Latin America analyzed the U.S. Consolidated Counterdrug Database (CCDB), granting insight into drug trafficking volumes.

In 2018, it was estimated that 210 metric tons of cocaine flowed through Venezuela. Although this number is significant, it pales in comparison to other routes—2,372 tons directly trafficked out of Colombia. Since Maduro took office in 2013, the two routes have consistently maintained a 9:1 ratio. In the same year, over 1,400 metric tons were tracked through Guatemala, a considerably smaller nation, while the Mexican land route was estimated to have managed 2,000 metric tons, according to the State Department.

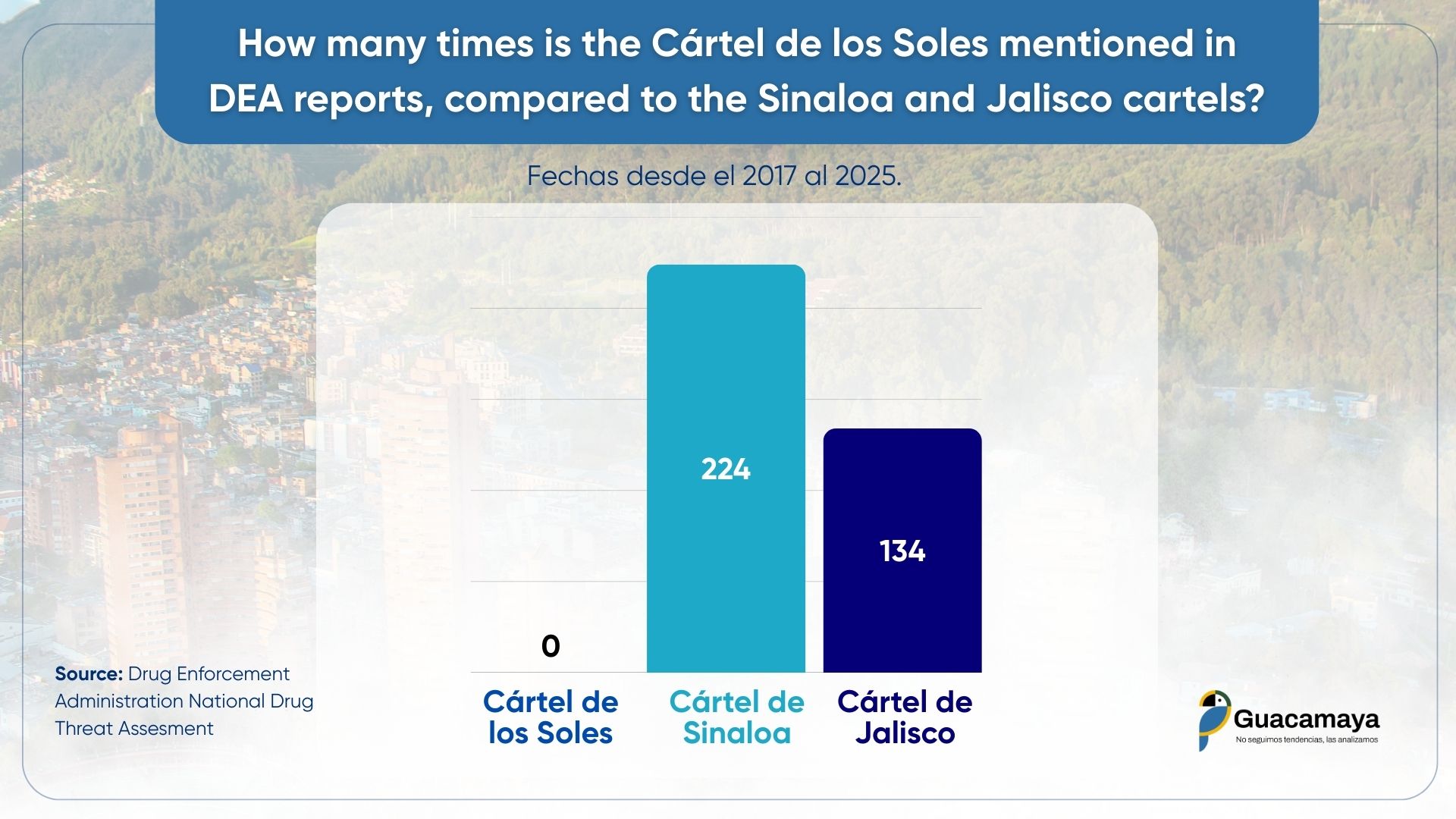

The two most recent National Drug Threat Assessments by the DEA (2024 and 2025) explicitly state that the entities wielding substantial control over narcotic trafficking to the U.S. are the Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG), both of which extend across 40 to 50 countries with their strategic ports and financial networks. None of these evaluations reference the Cartel de los Soles—or “Cartel of the Suns”—nor do they identify Venezuela as a significant threat or core player in drug trade.

When it comes to trafficking towards Europe, investigations have identified the Pacific and Atlantic routes, utilizing major port infrastructures while bypassing traditional and heavily monitored paths. In 2023, the port in Antwerp reported the removal of 121 tons of cocaine, the majority originating from Colombia and Ecuador. A Europol report from 2022 indicated that the leading points of departure are Brazil, Ecuador, and Colombia, while other nations like Chile, Panama, Peru, or Venezuela lag far behind. The Financial Times has labelled the Amazon rainforest as a “superhighway” for cocaine on route to Europe, with Brazilian mafias like Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) and Comando Vermelho contending routes against Mexican cartels.

A structural problem in the region

The drugs trade in Latin America stands as primarily a structural issue. This region is one of the most unequal globally, marred by high rates of poverty and social exclusion, as per the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). Factors such as vast, unmonitored landscapes, porous borders, and a persistent demand primarily in the U.S. and, later, Europe and other industrialized regions, further exacerbate the situation.

An officer from the National Police participates in dismantling a cocaine lab near Tumaco, Colombia, in 2008. Photo: Policía Nacional de Colombia.

An officer from the National Police participates in dismantling a cocaine lab near Tumaco, Colombia, in 2008. Photo: Policía Nacional de Colombia.

Geography plays a crucial role here. Extensive forests and mountain ranges, along with sprawling coastal areas, facilitate clandestine operations. The Andean-Amazonic region not only favors coca cultivation but also serves as a haven for hiding labs and export channels.

The financial gains from cocaine production, and even more from trafficking, are staggering. InsightCrime estimates that the surge of 600 tons in Colombian output from 2018 to 2022 translates to $1.2 billion at source prices, and no less than $20 billion on global wholesale markets.

All these conditions have collectively created an ideal breeding ground for highly lucrative illegal economies to thrive. Cocaine is merely one aspect, alongside illegal mining, human trafficking, and other illicit undertakings.

Venezuelan government officials and the drug trade: A cartelised network or isolated corruption?

In our investigation, we discovered that the Cartel de los Soles originated back in 1993 as a journalistic term used for a set of generals collaborating with the CIA. At that point, there was no proof of a consolidated criminal entity within the Venezuelan government or military.

However, the contemporary narrative of the Cartel de los Soles promoted by the State Department asserts that senior Venezuelan officials spearhead a “narco-terrorist” organization “using cocaine to inundate the United States.”

This accusation was officially made on March 26, 2020, by U.S. Attorney General Bill Barr, charging President Nicolás Maduro, Defence Minister Vladimir Padrino López, then-economy Vice President Tareck El Aissami, and National Constituent Assembly leader Diosdado Cabello among other Venezuelan officials along with leaders from the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC). Despite the seriousness of these charges, neither the initial nor the repeated accusations in 2025 were backed by tangible evidence; all that has been provided are vague accusations.

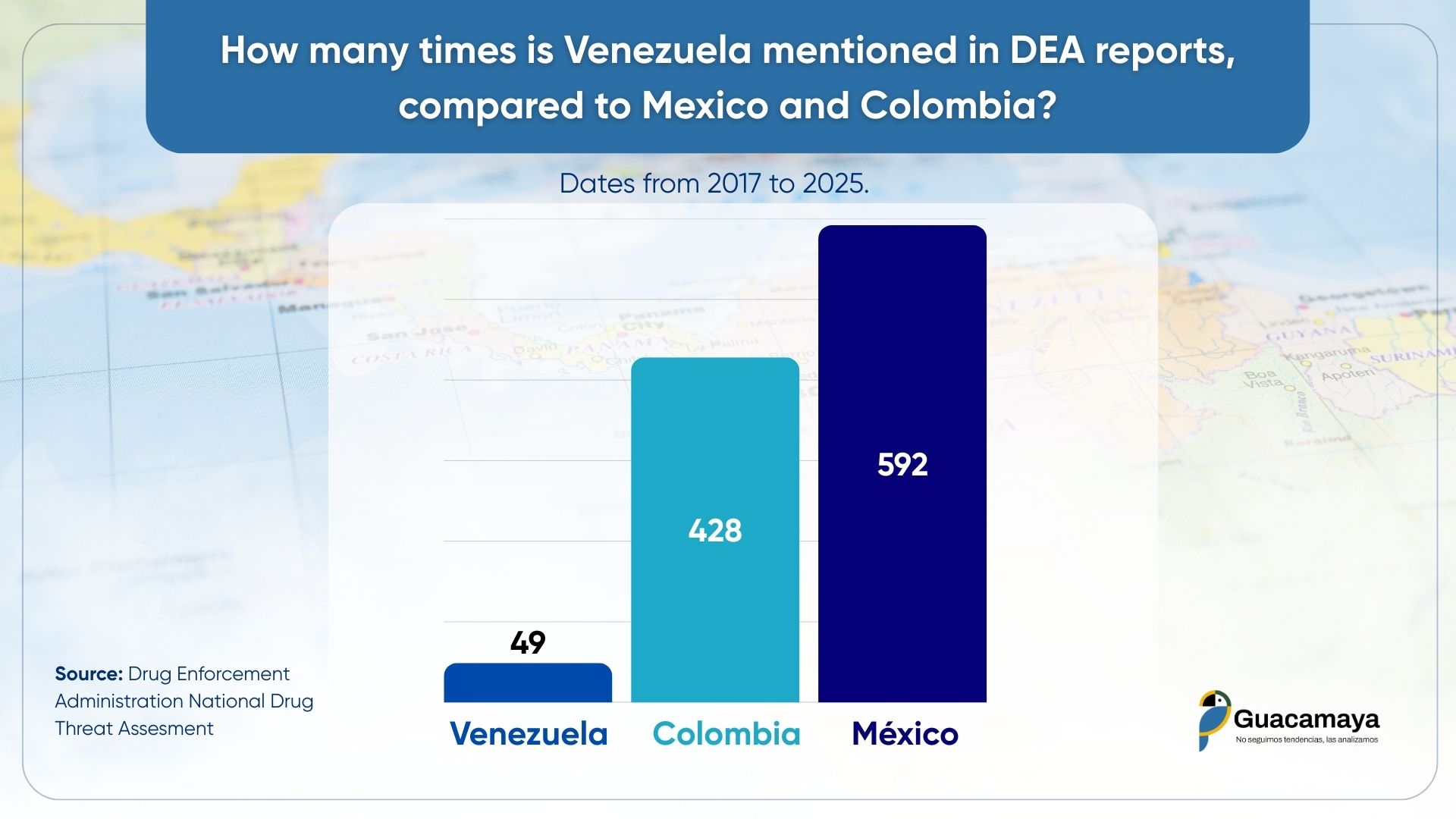

Recent National Drug Threat Assessments from the DEA, spanning 2017 to 2025, bolster the view of Venezuela as a minor player in cocaine trafficking, trivial when stacked up against other drugs. The nation is named 49 times in these reports, compared to 428 mentions for Colombia and 705 for Mexico. The “Cartel de los Soles” doesn’t appear at all, considerably undermining the Justice Department’s charges. In the same vein, the DEA refers to the Sinaloa Cartel 224 times, echoing the findings of the UN and European Parliament that label Venezuela as a minor producer while its role in international routes remains secondary, far removed from the Eastern Pacific corridor.

What cannot be disputed is that drug trafficking operates within Venezuela, and there have been occasions of government and military officials working alongside criminals. Yet, this pattern is replicated throughout Latin America, exacerbated in large part by a recent economic downturn, where nominal GDP dropped from $372 billion in 2013 to $43 billion in 2020, according to IMF estimations.

High-ranking officials being bought off by drug trafficking organizations is not exclusive to Venezuela. In Mexico, we’ve seen cases involving former Secretary of Public Security Genaro García Luna, a key player in the “war on drugs” from 2006 to 2012, who later faced trial and was convicted for colluding with the Sinaloa Cartel. General Salvador Cienfuegos, who served as Secretary of National Defence from 2012 to 2018, was arrested and charged for collusion with the Beltrán Leyva Cartel. Although charges were dismissed in 2020 “without prejudice,” indicating they could be reinstated, the federal judge overseeing the matter maintained it remains “solid.”

In Venezuela, the only senior government official who has been convicted in the U.S. for drug trafficking is Hugo “El Pollo” Carvajal, former head of the General Directorate of Military Counterintelligence (DGCIM) from 2004 to 2011 under Hugo Chávez, before briefly holding the position again from April 2013 to January 2014.

Carvajal was charged with facilitating and safeguarding the FARC within Venezuelan territory, enabling their establishment in uninhabited sectors of Apure and the smuggling of cocaine through the nation. Allegations suggest he received payments from Wilber “Jabón” Varela, a Colombian drug lord from the Cartel del Norte del Valle. Following Varela’s execution at the hands of his own cadre in 2008, Carvajal and other officials reportedly accepted payments from Mexican cartels.

In other cases, such as that involving Carlos Orense Azócar, a convicted trafficker, the setup included inducements to both civilian and military officials for allowing drugs to transit through Venezuela. Still, no evidence supports the notion of an organized, hierarchical cartel personally led by Maduro, or that he is systemically pushing cocaine into the U.S. Rather, there is a regional pattern of illicit trade infiltrating weak institutions.

Investigations from InsightCrime demonstrate that the narrative surrounding the Cartel de los Soles has been utilized to describe military corruption, even in the absence of evidence for widespread criminal collaboration: “It simplifies and distorts the drug trafficking situation in Venezuela—a Hollywood depiction of the Cartel de los Soles.” What surfaces most is a collection of accusations from U.S. politicians, lacking any substantiation from the DEA, UN, or other official reports.

A far more absurd assertion claims that Maduro is currently inundating the U.S. with drugs and arms by leveraging the Tren de Aragua. Initially a Venezuelan gang, it expanded throughout the Americas amidst the country’s mass emigration crisis. According to Geoff Ramsey from the Atlantic Council, “Tren de Aragua has morphed into a brand that any group of carjackers from Miami to Argentina can invoke to propel their criminal operations, yet there’s no clear hierarchy.”

Supporting evidence for these accusations is nonexistent. The 2025 DEA report dedicates a section to the group, marking its first mention since its designation as a “Foreign Terrorist Organization” by the Trump administration early this year. However, the NDTA asserts that Tren de Aragua “engages in modest drug trafficking activities, like distributing tusi. In certain U.S. locales, TdA members collaborate with larger criminal organizations conducting murder-for-hire schemes and serving as drug couriers, stash house guards, and street-level distributors.” The report fails to indicate that the gang is involved in large-scale operations, smuggling narcotics into the U.S., or taking orders from Maduro.

Compounding this, the U.S. intelligence agencies—including the CIA and NSA—have rejected the notion that Maduro orchestrates the Tren de Aragua. This accusation seems more aligned with the Trump administration’s immigration agenda, as it invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to advocate for mass deportations, more than addressing a genuine threat.

Colombian guerrillas: The actual players

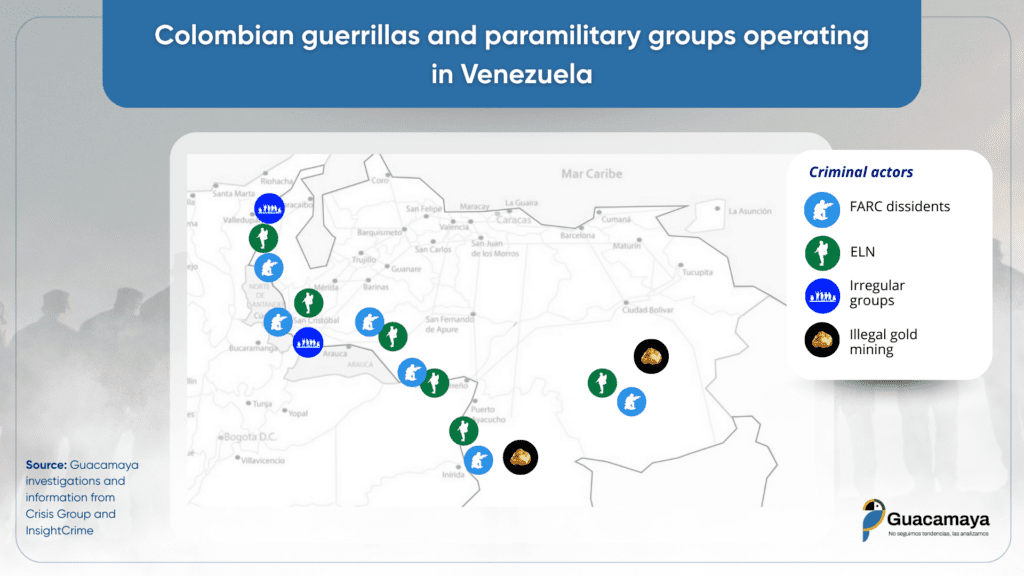

Various reports have thoroughly documented the presence of Colombian rebel factions operating within Venezuelan territory, particularly along the western and southern borders of Zulia, Táchira, Apure, Bolívar, and Amazonas. From 2010, these groups have pursued not only narcotics but have also been lured by a gold rush. This includes right-wing paramilitary factions, the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN), the FARC, and its splinter groups since 2017, like the collective known as “Segunda Marquetalia.”

These groups have become central players in Venezuela’s drug trade, taking advantage of the country’s institutional fragility. Moreover, they are also implicated in illegal activities such as gold mining, extortion, and human trafficking.

Their relationship with the state has been inconsistent. The Maduro administration has occasionally tolerated their presence in sparsely populated areas, especially after losing the ability to control all national territory due to a drastic drop in resources from 2014 to 2020. Nevertheless, they have also clashed. A notable instance was a confrontation between FARC dissidents and the Venezuelan military in March 2021 near the border town of La Victoria in Apure.

Carúpano: The euro rush

To better understand how drug trafficking operates in Venezuela, let’s head to the eastern state of Sucre, where drug trafficking has left significant marks. This region is among the poorest in the country, filled with tropical forests and mountains. It includes the Peninsula of Paria, which is a mere 10 km (6.2 miles) away from the island of Trinidad.

In the early 1990s, the phrase “pegó la vuelta” became commonly used in Carúpano, Sucre, referring to a smuggler successfully circumventing obstacles to transport drugs towards Europe. Consequently, euros began to circulate widely in the city. “You’d see euros just like bolívares,” says José, a local fisherman.

A view of Morro de Puerto Santo, a fishing village near Carúpano, an area long influenced by drug trafficking routes. Photo: Guacamaya.

A view of Morro de Puerto Santo, a fishing village near Carúpano, an area long influenced by drug trafficking routes. Photo: Guacamaya.

Since 2020, police and military units have intensified their crackdown on the drug trade in Sucre. In Macuro, the nearest town to Trinidad and Tobago, authorities seized 790 kilos of cocaine in a single operation in February 2025. The euro and other foreign currencies have become much less common, although some trafficking persists.

While criminal organizations adapt, the narcotics trade has caused intriguing local phenomena, giving us insight into how the drug trade truly operates in Venezuela.

José notes that security forces’ operations against local drug smugglers have impacted the local economy. Standing by the shore, he confidently states: “There’s no secret that these coasts were exploited for drug trafficking, but after the continuous arrests, that’s declining.”

A resident of Carúpano displaying various currency notes from different nations, including euro and pound sterling. They recount a past when Sucre’s beaches served as a crucial stop for cocaine trafficking from Colombia to Europe. Photo: Guacamaya.

A resident of Carúpano displaying various currency notes from different nations, including euro and pound sterling. They recount a past when Sucre’s beaches served as a crucial stop for cocaine trafficking from Colombia to Europe. Photo: Guacamaya.

A common trend across Latin America is the control these illegal activities assert on local economies, introducing new incentives for operation. José mentions that traffickers typically resort to bribing government officials who earn meager wages.

“It’s been years since I’ve last seen a euro. Sometimes, I go weeks without encountering a dollar, a stark contrast from when it used to be routine to receive them weekly,” he recounts. This illicit economy has, however, created indirect job opportunities: “Those in this trade injected capital into construction and other ventures to launder money. As that diminished, many found themselves without jobs.”

A local dentist has also observed the decline in euro transactions. In the past, he shares, “patients from San Juan de Unare, San Juan de las Gandolas, and El Morro de Puerto Santo would come in and pay in euros or dollars without hesitation.” The current scenario is starkly different: “Now, they only come when they truly have health issues. They come in around the 15th every month to collect government payments.”

In Venezuela, state employees, pensioners, and some in the private sector receive extremely low wages, with the minimum wage resting at just 130 bolívares— far below a dollar. This makes them heavily reliant on government bonuses that can total around $100.

A gym trainer highlights that customers once arrived in flashy cars, with high-quality cell phones and golden jewelry. They would pay with 50- or 100-euro notes, which are now seldom seen even on European streets. “Now, it’s mostly in bolívares, occasionally in dollars,” which has become a more common sight in Venezuela’s semi-dollarized economy. “The money moving around now is more ordinary, more linked to legitimate work, unlike before when it was tainted.” The locals’ narratives indicate a clear correlation: the rise and fall of the drug trade has reshaped their social and economic landscape.

False accusations have consequences

A long history of misconduct exists among Venezuelan government officials. Specifically concerning drug trafficking and corruption, multiple cases have emerged, even leading to convictions. There’s no need to fabricate false narratives to criticize Maduro. Genuine issues persist regarding his governance of the economy and his treatment of political adversaries. Instead, the State Department seems to be framing Venezuela’s crises merely as law enforcement matters.

By propagating serious assertions devoid of substantial proof, the U.S. government risks damaging its own credibility. Key regional allies, like Mexico and Colombia, have already dismissed these allegations. Will this jeopardize genuine cooperation required for combating drug trafficking?

We know the trajectory false political narratives can take. In 2003, the U.S. government fabricated a story regarding Iraq harboring weapons of mass destruction, which was subsequently used to justify invasion. This led to untold deaths and irreversible damage to Iraq.

We already see the first casualties. The narrative surrounding the Tren de Aragua gang is being exaggerated and manipulated to suppress the rights of Venezuelan and other Latin American migrants, primarily consisting of ordinary, industrious individuals.

Critical questions arise: Why is this false narrative being reinforced so vigorously? And why now? These inquiries will form the basis for a follow-up investigative piece to be published soon.