Venezuela boasts the largest gas reserves in Latin America, yet lacks the capacity to export. Currently, it faces a historic opportunity to develop its gas sector and enhance regional integration through gas pipelines.

Guacamaya, October 13, 2025. Gas has never been a priority for Venezuela. The planet’s largest proven oil reserves have overshadowed the country’s significant wealth of other resources, causing many to overlook the 221 trillion cubic feet of gas beneath its soil.

While Venezuela has usually been self-sufficient in gas, it has had to import it at times. The government has not prioritized capturing associated gas or developing large free gas fields, focusing instead on “black gold,” which offers greater profits. Gas should be viewed not only as an economic asset but also as a means of fostering regional integration.

Countries like Russia and China understand the importance of “hard connectivity” established by pipelines, which is fundamentally different from the “soft connectivity” of maritime oil trade. This understanding holds the key to making Venezuela a vital player in the region.

Venezuela currently faces two main challenges: firstly, how to create the infrastructure to connect with neighboring countries that are in urgent need of gas, and secondly, how to capture the gas being produced that is wasted through venting and flaring.

All of this occurs under unilateral sanctions from the United States, which hinder Venezuela’s ability to attract financing. The solution lies in establishing a national gas market to encourage private investment, which is supported by the current legal framework.

The Need for Venezuelan Gas Among Neighbors

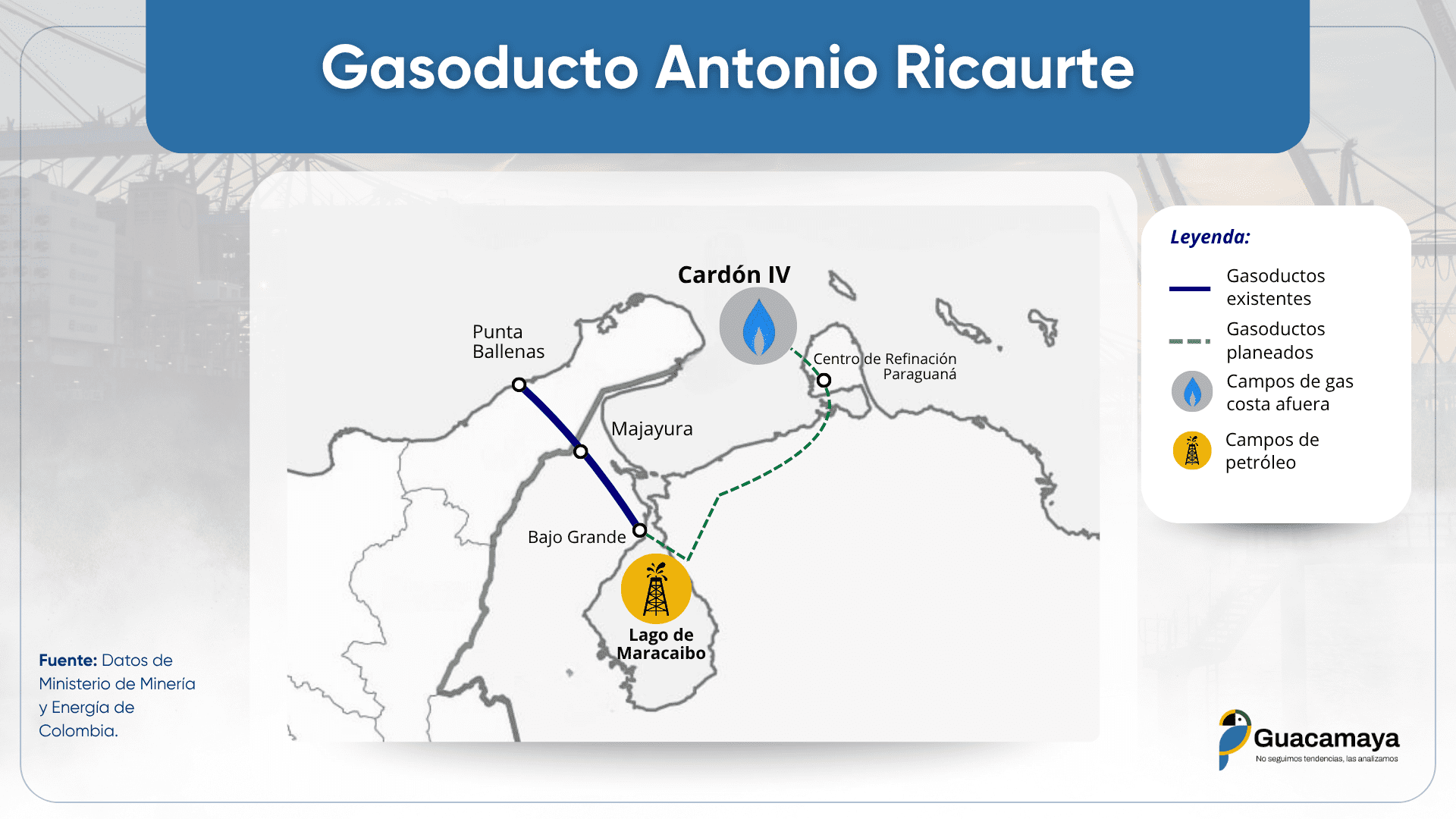

Many find it hard to believe that Venezuela’s neighbors actually need its gas. Colombia, along with Trinidad and Tobago, are significant gas producers. During President Hugo Chávez’s administration, the Antonio Ricaurte gas pipeline was even employed to supply Zulia with Colombian energy. However, both countries have overestimated their gas reserves and are now desperately searching for alternatives.

Globally, gas demand is projected to keep increasing, potentially rising by 32% by 2050. In Latin America, gas demand is estimated to increase by 83% from 2023 to 2035, growing from 150 billion cubic meters to 275.

Emerging economies continue to expand, and advances in technology significantly drive energy needs, particularly in Artificial Intelligence (AI). Furthermore, several nations are striving to reduce their reliance on oil and coal as they progressively embrace the energy transition.

In this backdrop, Venezuela is critical. Holding 221 trillion cubic feet, it possesses 78% of the gas reserves in Latin America and the Caribbean, according to BP. Yet, if Venezuela does not capitalize on this opportunity, countries will seek other sources. In Colombia’s case, this may mean resorting to fracking and coal, while Trinidad and Tobago has already signed agreements to develop gas fields with Guyana and ExxonMobil.

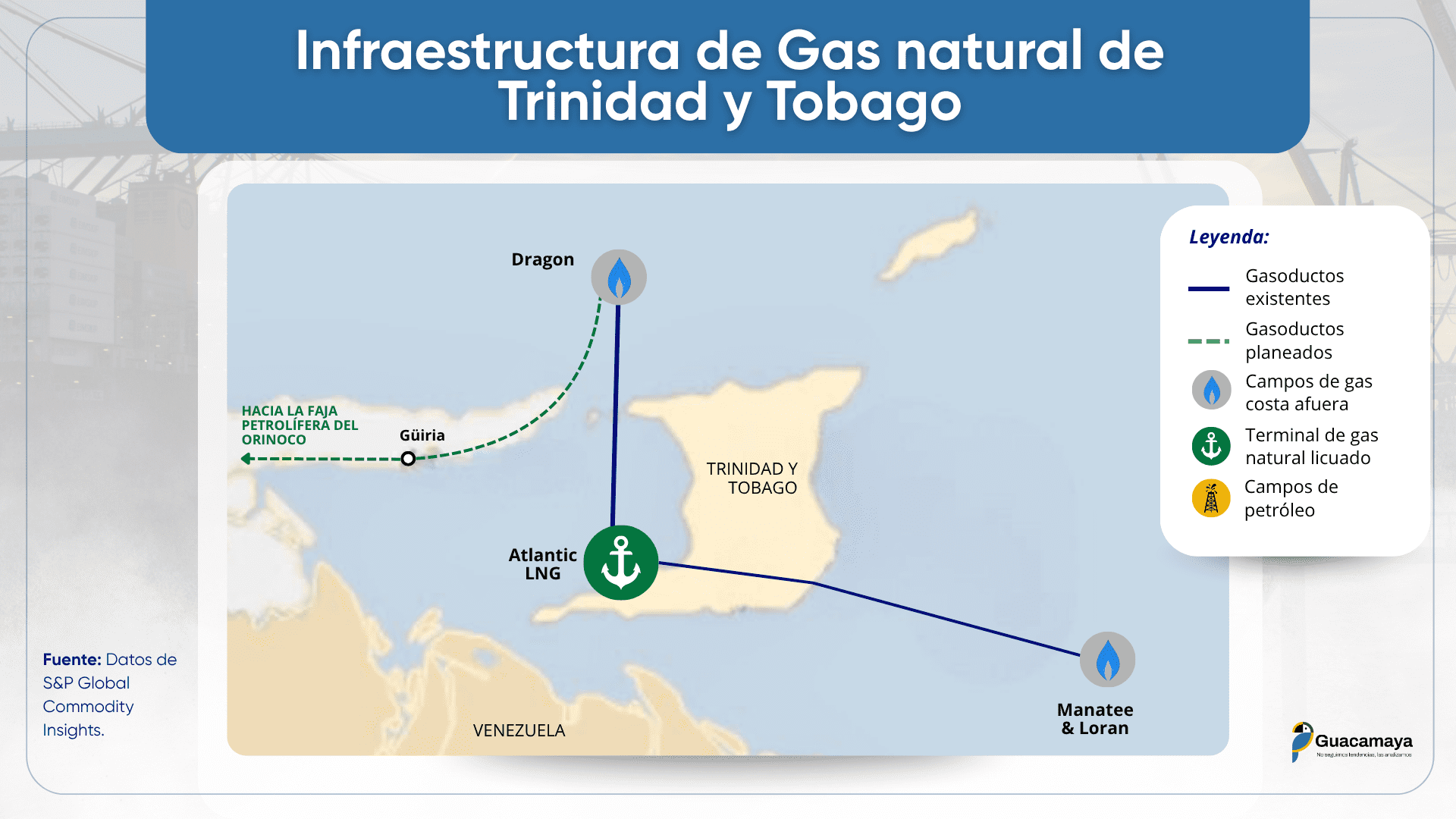

Since 2016, Colombia has been a net importer of gas, with the United States supplying 60% of its needs, while Trinidad and Tobago provides the remaining 40%. However, both suppliers have their issues. Liquefied natural gas (LNG), particularly from North America, is more expensive. Meanwhile, Trinidad and Tobago, though able to assist Colombia for now, will soon face its own production deficit. The island expects it has roughly 10 years of gas production remaining, factoring in its proven and probable reserves.

Trinidad and Tobago is grappling with an existential dilemma. Gas comprises 80% of its export revenue. It has built substantial infrastructure to export gas, and its national industries, such as steel and petrochemicals, rely heavily on it. A decrease in production would severely impact the entire economy.

The existing deficit is apparent: with a capacity of 4 billion cubic feet per day (BCFd), it only produces 2.6 BCFd. The island has already had to stop operations on one of its gas liquefaction trains, out of a total of four. Hence, accessing reserves in the exclusive economic zones of neighboring countries is of strategic importance. While Venezuela is the closest and most promising source, there’s also interest in Guyana, Suriname, and Grenada.

Proof of the necessity for Venezuelan gas is that both Colombia and Trinidad have attempted to secure special waivers from Washington to access it despite sanctions. Bogota is seeking to activate the Antonio Ricaurte gas pipeline, linking La Guajira to Zulia, while Port of Spain aims to connect the large gas fields of the Deltana Platform in Venezuelan waters with its own.

Moreover, we can see that Colombia’s President, Gustavo Petro, has maintained a cordial rapport with Venezuela, defending it against U.S. interference, although he does not officially recognize Nicolás Maduro as head of state. This is partly due to his expectation of being able to reactivate the binational gas pipeline.

Even the U.S. recognizes the need for Venezuelan gas. Colombia and Trinidad, along with other countries in the region, require not just more energy, but reliable and affordable sources. In this context, pipelines emerge as the solution. Meanwhile, North American companies can sell their LNG in Europe at higher prices.

The gas crisis has already triggered initial consequences: Colombia is reverting to coal, and its usage is expected to grow by 2026. This signifies a significant setback in the energy transition. Conversely, if fuel demand continues to rise without adequate supply, price surges may lead to instability and increased migration northward.

Hard Connectivity: Lessons from Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin

This presents a missed chance for Venezuela. It could capitalize on its neighbors’ needs to establish trade bridges resulting in strategic partnerships. The essential term here is “hard connectivity.”

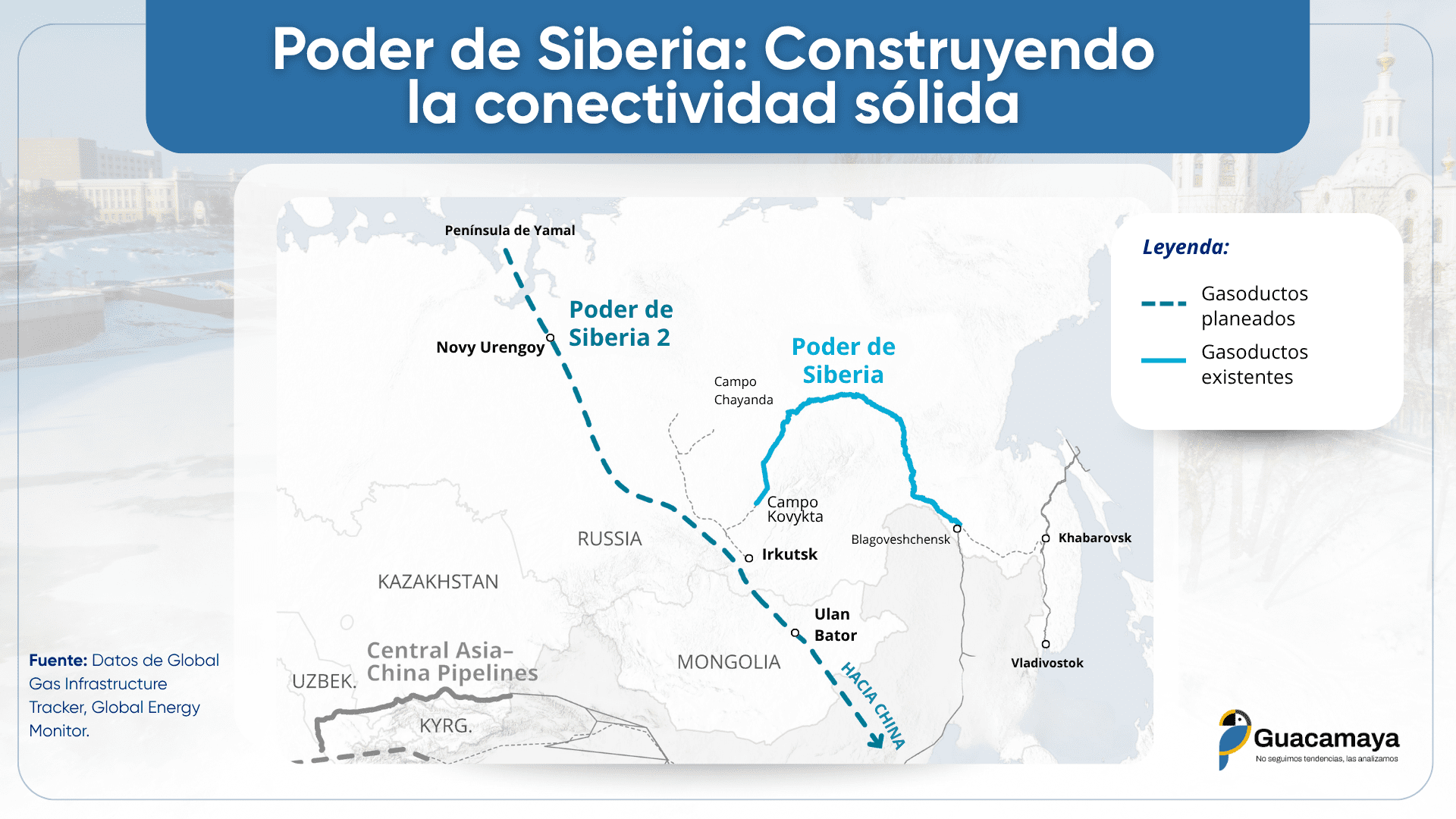

Consider the plans for the “Power of Siberia 2” gas pipeline. This pipeline will connect gas fields in the Yamalia-Nenetsia Autonomous District to China via Mongolia. These deposits, located in the northwestern region of enormous Siberia, were previously directed toward Europe.

Why is this pipeline of such importance? It aims to disrupt Russia’s hard connectivity to Europe and replace it with that of China. The pipeline is designed to transport 50 billion cubic meters (BCM) of gas annually, with an expected lifespan of at least 30 years. Before the Ukraine conflict, Europe imported nearly 200 BCM each year. With the Power of Siberia 2, China will receive 106 BCM per year through direct pipelines.

Regarding the new project, Chinese President Xi Jinping expressed that “‘Hard connectivity’ should be a primary focus, actively promoting cross-border infrastructure and energy projects linking the three countries.”

Natural gas presents a significant difference from oil. The latter facilitates “soft connectivity,” as transporting it in tankers is more efficient. These can be directed anywhere globally. While it is also possible to liquefy and cool gas, this incurs higher costs. The fastest and most cost-effective way to export gas is through pipelines, compelling the involved countries to commit for decades.

In 2022, as Russian forces approached Kiev, the decision was made in Brussels to stop purchasing energy from Moscow. However, this is not straightforward and is being very gradually implemented. In 2021, 40% of pipelined gas came from Russia. After extensive reductions, by 2024, 11 % still came from Gazprom. Sanctions have waited. The rationale: U.S. LNG is twice as expensive as Russian pipeline gas and several countries in Central and Eastern Europe lack the necessary infrastructure.

Currently, while Venezuela enjoys immense natural wealth, it remains largely irrelevant on the global stage unless it alters its perspective. Neighboring countries aren’t interested in gas they can’t purchase, nor do they see oil, available in numerous other markets, as strategic. The United States can afford to impose sanctions on Venezuela, just as Europe, Latin America, and India accept this unilateral action. However, when they require a stable, affordable, and efficient energy supply, priorities shift.

The Solution: Establishing a Gas Market for Regional Integration

Gas represents a broad opportunity for Venezuela. However, it is not being regarded with the significance it deserves. Decision-makers are primarily focused on the internal issue of producing cheap or free gas. The wholesale price is regulated at the lowest level in the region, averaging $1.4 per million BTU, while it is provided at no cost to the general population, including affluent families. Additionally, the collection problem persists among both public and private entities, severely undermining the sector’s profitability.

A clear lack of vision is present. Gas could serve as a means for regional integration, strengthening ties with Latin America and the Caribbean. Through oil’s soft connectivity, Venezuela is not competitive. Neighbors can procure oil effortlessly from anywhere in the globe. However, with the hard connectivity offered by gas pipelines, Venezuela can forge enduring links that withstand the test of time.

The reality of the current policy is evident: companies will not invest in gas if they can’t cover their expenses and make profits. If PDVSA intended to invest in gas production, this issue would not exist. The government could absorb any losses.

Nevertheless, this isn’t the case; all public corporation investments are channeled into oil. It’s more lucrative, and Venezuela desperately needs foreign currency. Moreover, because of unilateral U.S. sanctions, the Venezuelan government struggles to raise capital in international financial markets or multilateral institutions.

So, why not allow private firms to invest in gas? They could provide the necessary capital and shoulder the risks. The current legal framework supports it: the Organic Law on Gaseous Hydrocarbons enacted in September 1999 during Hugo Chávez’s presidency is still effective.

There already exist private companies producing gas independently of the state, as permitted by law and the Constitution. Currently, total gas production stands at 1.7 trillion cubic feet per day. Of that, 1 is a byproduct of PDVSA’s oil extraction and its joint venture partners, while the remaining 0.7 is free gas, from fields such as Cardón IV where Eni and Repsol share a 50-50 partnership. Near Trinidad, Caracas has also sanctioned projects involving major corporations like BP and Shell collaborating with the island’s National Gas Company, covering the Dragon, Manatee, and Loran offshore fields. Unlike oil, PDVSA’s involvement as a partner isn’t necessary; firms need only pay taxes and royalties as dictated by law.

Boosting gas production in Venezuela can be done far more swiftly and easily than in other nations by starting with capturing associated gas. The country produces and consumes 1.7 BCFd, while actually extracting 4 BCFd from its subsoil. Regrettably, all that excess gas is flared and vented, wasting it into the atmosphere with all the environmental repercussions and without any economic gain. Frustratingly, with just a fraction of this surplus, Colombia and Trinidad and Tobago’s domestic demand could easily be met.

The crucial step is for consumers profiting from gas, whether public or private, to start paying for it. The new scheme is yet to be defined; the government could continue subsidizing prices for lower-income families, for instance. However, zero or preferential costs are currently available to both middle- and upper-class families, as well as to public entities and major private companies.

The commercialization of gas also necessitates investments for operation, including meter installation, piping, marketing, and customer and collector networks. The state can let the private sector handle the capital and work involved.

The benefits are numerous, aside from the potential to generate a gas surplus for export to international markets, yielding foreign currency for producers and the treasury. Investing could lead to direct gas supply in urban areas, replacing cylinders. This change would lower costs and improve the quality of life for citizens.

Transitioning from liquefied petroleum gas and diesel to direct natural gas would also give a boost to national industries reliant on power from power plants. Consider the agricultural sector in Acarigua, Portuguesa. While diesel ranges from $15 to $20 per million BTU, direct gas could be delivered for $7 per million BTU.

The regional integration fostered by pipelines doesn’t depend on whether gas is produced by PDVSA or a private firm. The essential goal is to generate hard connectivity between nations, fostering a bond that strengthens ties among neighboring countries for decades to come. Ultimately, the state will always reap the most significant benefits.