Incumbent President Irfaan Ali is widely expected to win the general elections in Guyana again on September 1. Photo: Office of the President (Guyana).

Guacamaya, August 29, 2025. Guyana is heading towards the general elections on September 1, 2025, amidst a climate of high internal and regional tension. As an emerging oil power, Guyana is voting in light of disputes over the Essequibo with Venezuela, the influence of big oil companies, and the scrutiny of military partners like the United States and the United Kingdom. The results will impact not only local governance but also hemispheric energy security and the geopolitical landscape of the Caribbean.

How do elections work in Guyana?

General elections in Guyana are set for September 1, 2025, to fill the 65 seats of the National Assembly while electing the President. This early election follows the dissolution of parliament by President Irfaan Ali on July 3, 2025.

The National Assembly employs a proportional representation system with closed lists, consisting of 40 seats in a national constituency and 25 across 10 sub-national constituencies, allocated by the Hare quota. The head of state is selected via a simultaneous two-tier vote, with each list presenting its presidential candidate.

Reflecting on the 2020 elections, the PPP/C reclaimed power with 33 seats and 50.69% of the vote; the APNU alliance with the AFC secured 31 seats with 47.34%; and the LJP–ANUG–TNM alliance won 1 seat with 1.13%. The counting process was delayed for four months due to efforts perceived as manipulating the results favorably towards the ruling coalition.

With a population of around 850,000, approximately 750,000 residents are eligible to vote in a single round, with the winning party’s candidate being crowned as president.

Candidate Aubrey Norton (PNCR/APNU) represents the main opposition force to Irfaan Ali. Photo: Aubrey Norton Campaign.

Candidate Aubrey Norton (PNCR/APNU) represents the main opposition force to Irfaan Ali. Photo: Aubrey Norton Campaign.

The Candidates

Ethnic and partisan fragmentation remains prominent in Guyana, with Indo-Guyanese traditionally backing the PPP/C and Afro-Guyanese supporting the PNCR/APNU. However, the oil boom and security considerations might lead to shifts in voter preferences.

The ruling party (PPP/C) is retaining its ticket with Irfaan Ali and Mark Phillips. General Secretary Bharrat Jagdeo stresses the government’s efforts and management of the oil surge. Their campaign’s core message focuses on sovereignty, national security, and growth continuity.

The opposition (APNU) presents Aubrey Norton, the PNCR leader, teamed up with Juretha Fernandes. Their platform emphasizes transparency, a “patriotic front” against perceived threats to territorial integrity, and equitable revenue distribution.

As a third option, businessman Azruddin Mohamed is challenging the two-party structure. He has built a significant fortune in gold mining but faces U.S. sanctions for tax evasion. He has been accused of being a “puppet candidate for Maduro” by a U.S. congressman, which he refutes, claiming the government is using lobbyists in Washington to undermine him.

Electoral Alliances:

On May 30, the APNU formed an alliance with The Working People’s Alliance (WPA). On June 29, WIN merged with ANUG under Mohamed’s branding while retaining its legal identity. On July 1, the Forward Guyana coalition was created uniting The People’s Movement and the Vigilant Political Action Committee. Image from the campaign of Azruddin Mohamed (right), the gold sector businessman trying to position himself as a third political force. Photo: Azruddin Mohamed Campaign.

Image from the campaign of Azruddin Mohamed (right), the gold sector businessman trying to position himself as a third political force. Photo: Azruddin Mohamed Campaign.

An Oil Economy with High Social Expectations

Once considered one of the poorest nations in the region, Guyana is now experiencing tremendous economic growth following the discovery of oil reserves offshore.

The Stabroek block, containing 11 billion barrels, gives Guyana the highest per capita oil reserves in the world. Oil extraction began in 2019, hitting 650,000 barrels a day this year, with expectations to reach 1 million per day by 2030.

The country’s GDP has seen double-digit growth since 2020, soaring 63% in 2022 and 43.6% in 2024, the highest in the region. Guyana’s GDP per capita stands at $32,300—eight times that of Venezuela, according to the IMF.

However, experts point to what is termed the paradox of abundance, where, despite the oil boom, social and infrastructure issues linger. The crucial challenge is to convert oil revenues into sustainable well-being through transparent governance, sovereign funds, and clear regulations.

The Essequibo: A Campaign Issue

Understanding the significance of this matter requires a look at the historical context of Venezuela’s claims: they argue that the Essequibo belonged to the Captaincy General of Venezuela and that the 1899 Paris Arbitral Award—which allocated the territory to British Guiana—was null and fraudulent, influenced by pressures from imperial powers. The Geneva Agreement (1966), signed with the UK and newly independent Guyana, acknowledges this dispute and instructs negotiations for a mutually acceptable resolution.

From Caracas, officials assert that mining and oil concessions in the contested area disrupt the status quo, violate the Geneva Agreement’s spirit, and set unfavorable conditions for negotiations. The offshore expansion associated with the Stabroek block exemplifies this concern.

A lesser-known precedent in international discussions regarding this issue is the obscured Rupununi Rebellion of 1969.

In January 1969, Amerindian communities and ranchers from the Rupununi region, south of the Essequibo, revolted against Georgetown due to neglect and rights violations while expressing solidarity with Venezuela. The rebellion was swiftly crushed with violence and logistics support from outside; numerous leaders fled to Venezuela for refuge.

This episode, for Venezuela, demonstrates that segments of the population do not fully identify with the Guyanese state, reinforcing the view that the Essequibo remains a territory not firmly under Georgetown’s control, but instead an area with cultural, geographical, and political ties to Venezuela.

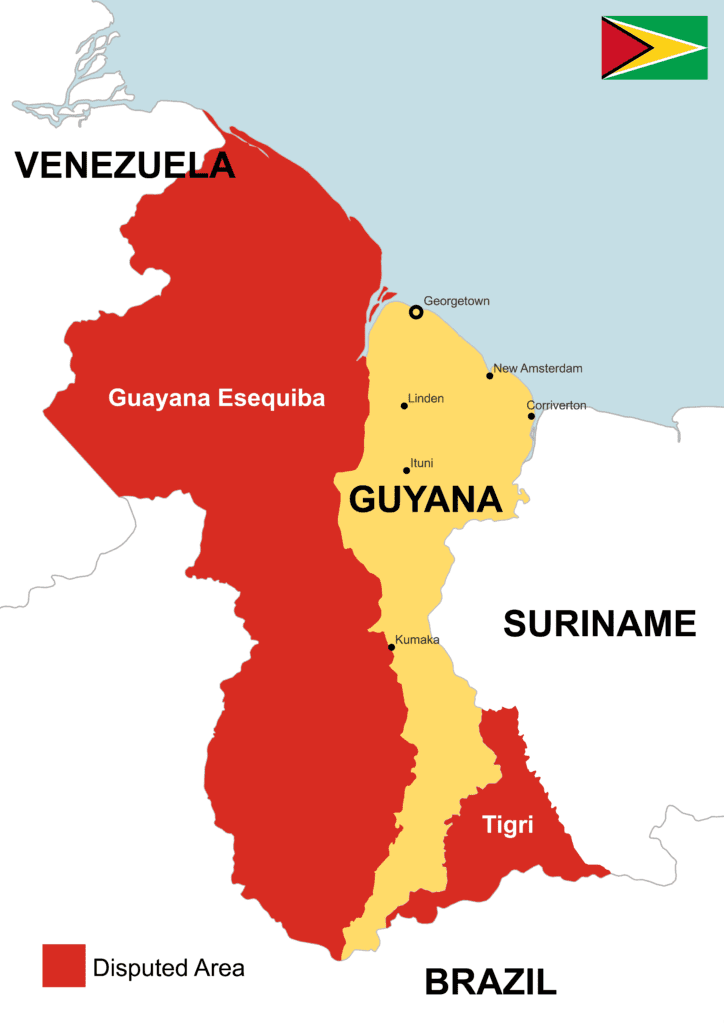

Venezuela argues that its border with Guyana should be at the Essequibo River, which would cut away 70% of the territory currently under Georgetown’s control, although only affecting 15% of its population. Suriname also lays claim to the Tigri area. Map: SurinameCentral.

Venezuela argues that its border with Guyana should be at the Essequibo River, which would cut away 70% of the territory currently under Georgetown’s control, although only affecting 15% of its population. Suriname also lays claim to the Tigri area. Map: SurinameCentral.

Oil Companies with Interests in both Venezuela and Guyana

Interestingly, several energy firms have operations or interests on both sides of the Essequibo territorial dispute.

ExxonMobil (USA): They lead operations in the Stabroek block in Guyana. In Venezuela, it has faced numerous legal challenges and conflicts over expropriations and concessions in maritime areas linked to Essequibo. The government of Venezuela accuses the firm of “funding the opposition” and “promoting sanctions against Venezuelan oil.”

CNOOC (China): CNOOC is a partner in the Stabroek consortium alongside Exxon in Guyana. In Venezuela, firms from China have formed strategic partnerships in oil upstream and refining projects, essential for Beijing’s energy diversification.

Chevron (USA): Chevron holds a 30% interest in Stabroek post its acquisition of Hess Corporation in Guyana. Despite challenges from ExxonMobil, they were granted a favorable ruling by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). In Venezuela, it is the sole U.S. oil company with OFAC licenses to extract and export crude under the sanctions regime, acting as a connector between Caracas and Washington.

Repsol (Spain): Repsol operates in Guyana through Repsol Exploration Guyana and manages the offshore Kanuku block. Despite disappointing results in some wells like Beebei-Potaro, exploratory activities continue. In Venezuela, it is a significant partner of PDVSA, having acquired special permits during the Biden administration that were strained under Trump. With backing from the Spanish government, it aims to resume Venezuelan crude marketing soon.

Spain aspires to diversify its energy supplies in light of ongoing tensions with Morocco and Algeria due to its shifted stance on Western Sahara, alongside impacts from the Ukraine war. Hence, both Venezuela and Guyana appear viable alternatives, as they aren’t located in high-tension regions like the Middle East. However, this perspective may be jeopardized by the Essequibo tensions.

Guyana’s Military Agreements

Guyana has fortified its defense strategy through significant agreements, particularly with the US and UK, to deter risks in its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and improve interoperability:

United States:

Shiprider Agreement (2020): Joint maritime/air patrols against illegal fishing, trafficking, and other threats. Acquisition & Cross-Servicing Agreement – ACSA (2021): Reciprocal logistics (supplies, maintenance, services) between the GDF and the Department of Defense. Regular combined exercises (coast guard and US Navy), exchange of ISR capabilities, and training, with public endorsements supporting Guyana’s territorial integrity.

United Kingdom: Naval deployments and exercises (including the HMS Trent) serve as deterrents and supportive gestures. There is also cooperation in training and maritime awareness.

Brazil: Brazil is increasing its military cooperation with Guyana and has proposed constructing a highway to Georgetown to gain access to the Caribbean.

The Venezuelan Position: Venezuela condemns the militarization of the dispute and external military support for Georgetown. Concurrently, Russia has criticized Western military involvement and has enhanced its collaboration with Venezuela, recalling prior agreements in territorial disputes like Abkhazia and South Ossetia during the 2008 Georgia war. Russian firms like Rosneft have previously secured concessions from Venezuela and have shown interest in the waters associated with the Essequibo maritime territory.

The United States and Guyana maintain close cooperative relations, especially in defense. In the image, Secretary of State Marco Rubio and President Irfaan Ali meet in Georgetown on March 27, 2025. Photo: Office of the President (Guyana).

The United States and Guyana maintain close cooperative relations, especially in defense. In the image, Secretary of State Marco Rubio and President Irfaan Ali meet in Georgetown on March 27, 2025. Photo: Office of the President (Guyana).

Election Observers

The OAS signed an agreement in July for the deployment of an Electoral Observation Mission (EOM) to supervise the September 1 elections, highlighting its constructive intentions with positive recommendations for enhancing institutions and public confidence.

The European Union mission, led by Robert Biedroń, comprises electoral experts and long-term observers ensuring thorough monitoring of the electoral process and its legal-administrative framework.

Given all these factors, one can argue this is a decisive election. Guyana is at a crossroads, choosing between continuity with the PPP/C, a change with APNU, or disruption with WIN. The victor will need to navigate the oil boom amid geopolitical stresses from energy demands heightened by uncertainties in the Middle East and the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Oil and geopolitical factors will be crucial in the upcoming cycle, shaped by investments in Stabroek and surrounding areas involving ExxonMobil, Chevron, CNOOC, and Repsol, which impact the stability of the Caribbean and the energy transition of major powers.

The Financial Times has characterized the situation in Guyana as the emergence of the world’s last petrostate during times fraught with significant conflicts. The neighboring nation is heavily reliant on the United States, particularly on ExxonMobil, which appears to be defining its interests in making Guyana a dependable energy supplier for the U.S. Meanwhile, the Essequibo remains a remnant of British colonialism, whose interpretation in the West seems to be swayed by Venezuela’s current position rather than a comprehensive historical context that various governments and international media seem to gloss over.